Posted by

Bradley Lands

on

competence

confidence

culture

knowledge-able

learning

responsive

teaching

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

"Learned helplessness is the giving-up reaction, the quitting response that follows from the belief that whatever you do doesn't matter." - Arnold Schwarzenegger

There is an old saying, "If you give a man to fish, he eats for a day. If you teach a man to fish, he eats for a lifetime." As educators, we ultimately want to teach our students how to fish. We want to help them acquire the knowledge and skills that will help them to become independent, lifelong learners.

The problem is that it's often much easier to provide an answer to a student's question, rather than teaching them how to find it on their own. Sometimes we feel like we don't have enough time to allow students to look up the answers. And other times we are tired of students asking the same questions over and over again—or we are too busy multitasking—so we just give in to them. Regardless of our reasons, we know deep down that in these moments we aren't helping our students develop the necessary skills to figure things out for themselves. This can lead to feelings of guilt and regret as a teacher.

From a student perspective, I totally understand why they would prefer to get the answer from a teacher rather than trying to find it on their own. For one, it's way easier to get the answer. And two, it can be a lot more comfortable to be told what to do. But sometimes it isn't a matter of effort. Sometimes it is a matter of confidence. For instance, some students might believe that they lack the ability to complete a learning task independently. Whereas other students might feel lazy and aren't willing to put in the work. We've all been there. I get it. But as teachers, we know that the most significant learning happens when we step outside of our comfort zone, and when we put in the mental effort to learn on our own.

I try really hard to build capacity in my students so that they have the confidence and the skills to answer their own questions. Especially trivial questions like, "How do you spell ...?" or "What is the definition of this word?". I try to encourage them to use resources such as books in the classroom, internet searches, and other classmates for help. By the end of each school year, I find myself getting frustrated when students ask the same routine questions that they already know the answers to. Stop me if you've heard these before: Where do I turn this in? What is our homework for tonight? or "I don't have a pencil," which isn't even a question.

Students definitely know the answers to these questions in my class, and I'm sure they do in your class too. They know where to turn in their assignments. They know where to check for homework. And they know where they can find extra classroom materials. Yet, they still ask these questions because they have somehow developed this sense of learned helplessness—repeated dependency on others to answer questions and solve problems for them.

When teachers continually provide the information that students request, they learn to become dependent on their teachers for answers. Every time we assist highly capable students with mundane tasks we are enabling and reinforcing their learned helplessness. Because of this, we delay our students' development of critical character traits such as responsibility—making their own decisions—and accountability—owning their actions.

In order to break this dependency cycle, we need to help our students build their confidence and learn to trust their abilities. We need to provide them with opportunities to engage in productive struggle and to support them as they develop skills to become more independent. That is to say, we need to help them to believe in themselves as learners.

One way that we can do this is to strategically support them in learning tasks that are above their ability level at the time of instruction. By introducing necessary information to increase their knowledge and skills, we can assist students in developing their abilities to overcome mental barriers. This theory is what Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky initially published as the zone of proximal development.

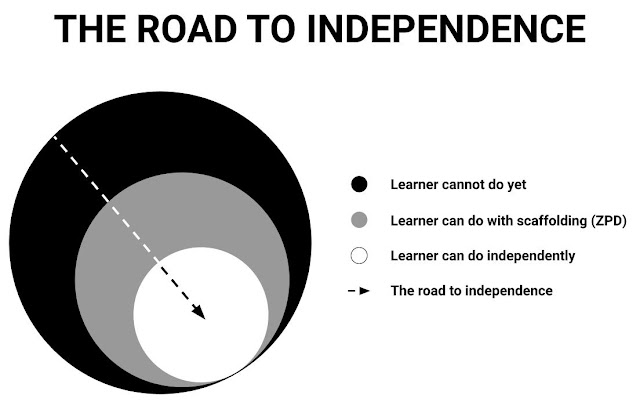

Vygotsky defines the zone of proximal development (ZPD) as "the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he or she can achieve with guidance and encouragement from a skilled partner" [1]. He claims that there are three specific zones in learning: what a learner cannot do yet, what a learner can do with scaffolding or support from a skilled partner, and what a learner can do independently (See Figure 1). The zone of proximal development refers to the middle ring in Figure 1—what a learner can do with scaffolding from a skilled partner.

| |

|

In Vygotsky's definition of ZPD, the term "proximal" refers to those skills that the learner is close to mastering. And the term "skilled partner" is commonly referred to as the teacher [1]. However, this skilled partner can be anyone—a parent, mentor, colleague, or friend—that has more knowledge on the subject matter. Vygotsky more specifically refers to a skilled partner as a more knowledgeable other (MKO), or anyone that has a better understanding of a given topic [1].

I agree with Vygotsky in that the most significant learning occurs in the zone of proximal development. This is where students engage in productive struggle and they have guidance and support from a teacher. However, I believe that this is also where students build their confidence as a learner. In this zone, teachers can provide the encouragement that students need to develop their abilities in problem-solving, as well as social-emotional skills.

Vygotsky believed that social interactions with a skillful tutor allow the learner to observe and practice their skills [1]. In other words, these social interactions help the student not only learn the content of the lesson, but they also gain critical people skills which can help to develop their independence. As a child seeks to understand the actions or instructions provided by the teacher, they internalize the information, using it to guide or regulate their own performance [1].

Learning is the Vehicle on the Road to Independence

Even though the most significant learning occurs in the zone of proximal development, I believe that our goal is to steer our students out of this zone, as they begin to accomplish learning tasks more independently. I like to think of this process as the road to independence where the vehicle on the road represents the learning progress of a student. The student begins their learning journey not knowing how to drive. But with the help of a teacher in the car, the student begins to learn how to drive, and eventually doesn't need the teacher in the car anymore, and can drive independently on their own.

As teachers, we essentially want our students to become self-sufficient so that they can apply what they learned in the zone of proximal development to new situations and challenges. If we are able to repeat this process for all of our students throughout the school year, then they will be better positioned to learn on their own.

If we are doing our job correctly, the role of the teacher should be gradually reduced over time. The more we help our students develop the knowledge and skills that they need to become independent learners, the less they actually need us. This is the purpose of the zone of proximal development. We want to provide enough scaffolding to our students so that they can successfully accomplish the learning task without us.

In the field of education, "Scaffolding consists of the activities provided by the educator, or more competent peer, to support the student as he or she is led through the zone of proximal development" [1]. In order for this to work correctly, the support needs to be slowly withdrawn as it becomes unnecessary, much as a scaffold is removed from a building during construction. The scaffold is slowly removed until the student can complete the task on their own [1].

For example, before I teach my students how to effectively perform internet searches, they often struggle with finding helpful information for their projects. Some students type in their questions exactly as they wrote them down, whereas other students don't provide enough words in their search to yield their desired results. But when I teach them the skill of using keywords in their search queries, they begin to find the relevant information they have been looking for.

Let's say that Aaliyah is a third-grade student and her class is studying endangered species that live in the Amazon rainforest. She decides that she wants to learn more about jaguars and why their population is decreasing. So she starts off by entering the word "jaguar" into a Google search. She is surprised to find that her results are not what she intended to find. She notices that results include Jaguar cars, which is not what she wants to read about. So she modifies her search and enters the word "jaguars" only to find information on the Jacksonville Jaguars NFL team. Aaliyah is now becoming frustrated as she is unable to find information on her endangered species.

In order to move Aaliyah into the zone of proximal development, the teacher provides some scaffolding by suggesting that she tries to include more keywords into her search query. The teacher hints at Aaliyah to add words that might be associated with a jaguar in the Amazon rainforest. With some help from her teacher, Aaliyah now performs the following search: "jaguar animal amazon rainforest endangered species." To her surprise she finally gets the results she has been looking for. And she discovers that jaguars aren't actually endangered in the Amazon rainforest, but they are threatened due to poachers and deforestation.

The act of scaffolding is so effective because it not only produces immediate results, but it also instills the skills necessary for independent problem solving in the future [1]. In the example that I shared, Aaliyah wasn't able to learn about jaguars because she didn't have the skill of performing effective internet searches. But when the teacher provided appropriate scaffolding, Aaliyah moved into the zone of proximal development and was able to adapt her search strategy to successfully retrieve her intended results. As Aaliyah continues to practice the skill of adding keywords to her future internet searches, she will slowly move out of the zone of proximal development, and into the zone of independence where she will build her confidence.

A Savvy Scaffolding Strategy

At the beginning of each school year, I not only like to get to know my students as individuals—their interests, personalities, and hobbies—I also like to get to know their learning preferences. Throughout the school year, I like to survey my students about how they think they learn best. Here are some questions that I have found to be highly effective for learning how my students like to learn:

Be Less Helpful

If we want to reduce our students' learned helplessness, sometimes we need to be less helpful. By providing too much information—giving students the answers—we are actually prohibiting them from thinking for themselves. What we should be doing is providing them with hints of helpful information, or asking them calculated questions that stimulate their thinking.

This can be really challenging because it goes against our natural instinct to want to help our students. But if we can resist this temptation—to help our students quickly reach a desired learning outcome—then we will be doing them a favor in the long run. In fact, research shows that “Anytime an adult feels it necessary to intervene in an educational transaction, they should take a deep breath and ask, ‘Is there some way I can do less and grant more authority, responsibility, or agency to the learner?’” [2]. And by granting more authority, responsibility, and agency to our students, we are empowering them to think for themselves, which will pay dividends in their ability to learn independently.

In Aaliyah's example, the teacher provided just enough information so that she could try the teacher's advice. The teacher didn't give her the exact keywords to use in her search. Instead, the teacher helped Aaliyah to facilitate her learning by asking her to think about words that might be associated with her topic. From there, Aaliyah was able to think about other words that might be relevant to her search criteria, and was able to yield positive results.

In this case, the teacher acted as a lead learner to the student, as opposed to a traditional teacher who has all of the answers. As a lead learner, the adult in the classroom promotes student independence by shifting the power to the learner. This helps to build strong relationships in a classroom learning community where everyone is interdependent on each other, and not solely dependent on the teacher.

I am always the first to admit to my students that I don't have the answers to everything. I think that it's extremely important for teachers to check their pride at the door when they walk into the school building. My goal as a lead learner is not to show my students how much I know—my goal is for my students to show me how much they know.

For example, whenever I find that my students are stuck and cannot make progress, I like to ask them the following questions to help them become more independent learners:

As a lead learner, I strive to cultivate my students' confidence and have them leverage learning tools that they will need to independently answer their own questions and solve their own problems. And to build a learning community in the classroom, I tell my students that I don't have all the answers for them, but that I will support them as they seek answers for themselves. Over the years I have found that these questions are highly effective at motivating students to take learning risks that will help to develop their problem-solving skills and build their confidence.

The Metacognitive Method

We learned in the Questions Have Always Been the Answer chapter that metacognitive thinking is necessary for learning to occur. Plenty of evidence suggests that "Students’ academic performance is linked to their ability to engage in thinking strategies, especially the metacognitive processes that make self-regulated learning possible" [2]. And as students learn more about their thinking, they also increase their ability to manage their own thoughts and may even begin to think about learning differently [2].It can be helpful to create a reflection checklist for your students as they engage in the learning process for each unit of study. This allows them to reflect on how much they have learned, how effective their strategies are, and what they need to do to continue making progress. Here are some reflection statements that I have found to be effective in helping students check-in with themselves on their learning and understanding:

I also challenge students to come up with their own reflection statements that might not be on this list. This allows them to take their reflection a step further by thinking about their own individual learning process. By empowering students to use this reflection strategy, I have discovered that they are more thoughtful and intentional in their learning. I have also found that when students value this reflection process, they become more independent, and less reliant on the teacher. This is because when students are able to make the connection between their choices and their learning outcomes, it reinforces their confidence in their ability to take ownership over their learning.

Promoting Learned Helpfulness

In a perfect world, all of our students will become independent learners and go out into the world equipped with the knowledge and skills that are required to accomplish anything they desire. In an attempt to turn this dream into reality, we need to help our students develop a new set of habits. We need to teach them to unlearn their learned helplessness, and help them learn how to help themselves. Put simply, we want our students to know what to do, when they don't know what to do.

I believe that we need to set high expectations for our students and hold them accountable for their success. But to ensure their success, we need to provide them with the appropriate support and self-regulated learning strategies along the way. If we can shift our thinking to approach teaching as promoting learned helpfulness, then our students will be better suited for making decisions, answering questions, and solving problems in the real world.

I hope that the strategies that I have shared inspire you to adopt—or adapt—them to help your students develop the initiative that they need to begin learning more independently. And I hope that you continue to find creative ways to help your students build the confidence that they need to abandon their learned helplessness and embrace a more self-sustaining outlook on their education. An outlook where they would rather learn to fish and eat for a lifetime, than be fed a fish to eat for a day.

Comments

Post a Comment