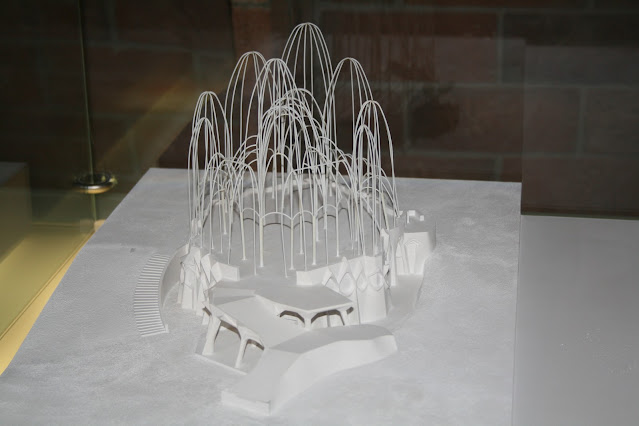

The most fascinating part of this story is that by using this brilliant technique, Gaudi was able to create naturally occurring geometric shapes and figures—catenary arches, atenoids, parabolas, hyperbolas and hyperboloids—that were used to design tall arches and high vaults to effectively support the weight of the building [2]. What's more, he even used the inspiration of nature to design interior elements by designing the core pillars of the main church to resemble tall trees with fanning limbs and branches to support the vaulted ceiling (See Figure 2).

Gaudi's design of the Sagrada Familia was so impressive that it eventually became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, among many of his other works. Because of his exceptionally creative and original designs, Antoni Gaudi became internationally recognized as one of the most prolific contributors to modernism.

So what can we learn from Gaudi's design process? I believe that when we are faced with challenges that have constraints, we need to be creative and think about the problem from multiple perspectives. In other words, we need to flip our thinking in order to innovate inside the box, just like Gaudi flipped his thinking by turning his upside down model, right side up. There will always be constraints for every project, but if we are able to think of our constraints as opportunities for creativity, then we will likely find inventive solutions to our problems.

Constraints in the Classroom

Each classroom in every school has its own unique constraints. School communities are made up of families with different cultures, backgrounds, values, religion, and financial resources. Some school communities are more diverse, whereas other school communities are more uniform. Regardless, each school has its own distinctive community that influences decisions that are made in the classroom.

What's more, within each school community we have common constraints that are found in our classrooms—time, space, materials, and policies. Each one of these constraints impacts the amount of learning that goes on in the classroom. Therefore, if we are able to find ways to innovate inside the classroom, then we can capitalize on our creativity to optimize student learning. Let's take a closer look at how we might be able to use each of the following classroom constraints to our advantage—even on a tight budget.

Time

I challenge you to find a teacher who says they have too much time in the classroom. My guess is that you probably wouldn't be able to, simply because time is the most valuable resource when it comes to learning. However, students and teachers are all bound by time throughout the school year. In every school, students are required to attend either a minimum amount of days, or a certain amount of hours in order to advance to the next grade level. Additionally, every school has its own bell schedule that dictates the amount of time students spend in each class every day. And within each bell schedule, more time is often dedicated to core classes—math, language arts, science, and social studies—as opposed to the special classes, or what I like to call "encore" classes—world language, music, art, drama, technology—that often receive less instructional time.

I have found that what matters less is how much time you have, and what matters more is how effectively you use this time. There are lots of ways that we can strategically leverage routines and expectations, as well as give up some of our control to our students in order to increase our efficiency. One idea could be establishing a routine where as soon as students walk through the door, they begin a learning task to minimize downtime. This could be in the form of a warm-up such as working on a prompt that is on the board, having students reflect on what they learned from the previous class, or picking up where they left off on a project. Another idea could be to assign different roles to students throughout the year so that they are collectively accountable for community responsibilities such as distributing and collecting materials, keeping track of time, managing group projects, and encouraging their classmates to stay on task.

Some teachers have even embraced the flipped classroom model of instruction. In this model, students receive online, direct instruction at home in order to create more time in the classroom for hands-on, experiential learning opportunities. Teachers who use this model often find that their students develop a deeper understanding of the content because they are using class time more productively. As you can see, when we empower our students to take ownership over their learning we can find ways to use our time more intentionally in the classroom.

Space

Classroom space can look completely different from school to school. A traditional classroom has four walls and is typically in the shape of a square or a rectangle. But in some parts of the world, classrooms can be located outside, or they even live in a digital space like online universities and virtual schools. In a traditional school, teachers are either assigned to a classroom at the beginning of the year, or—depending on other space and staffing constraints—they might have to wheel a cart around to other classrooms. However, this doesn't mean they can't optimize the space that they have, or even utilize other spaces as an extension of their classroom.

In their book, The Space, Rebecca Louise and Robert Dillon (2016) recommend that when teachers create learning spaces, they need to first start with what students will do, then figure out what stuff supports it [3]. And by "stuff" they are referring to things like furniture, structures and materials. They also point out that it is important to consider a layout and arrangement design that will best support student learning in that space. For example, in an inquiry-based classroom where students are encouraged to ask questions and investigate ideas, you might find shareable surfaces, flexible seating, and exploration stations. In order to create this type of learning environment, teachers can combine desks into tables, provide seating options with different heights around the room, and allocate areas of the classroom that are dedicated to curiosity, collaboration, or creativity. Some of these areas might include a wonder wall for posting ideas; a question corner for sparking curiosity; a campfire circle for sharing and storytelling; a novelty nook for imagination and creativity, a cafe counter for independent thinking, writing, and reflection, or a student studio for recording audio and video projects.

There are also other spaces that teachers can use outside of their formal classroom setting. For instance, teachers can take students outdoors to harness natural sunlight and fresh air to stimulate their thinking in a new environment. By intentionally bringing students outside, teachers can conduct specific thinking exercises to help students to inquire about their surroundings, make observations, walk around to find inspiration for ideas, engage in reflection under a tree, or have group conversations that don't require inside voices. And depending on the learning task, teachers could also use different spaces in the school such as an art room, a makerspace, a theater, a cafeteria, or a gymnasium. In addition, students could take field trips to learn from experts, explore landmarks, or visit museums. Furthermore, students could leverage digital spaces to connect with other classrooms around the world, embark on virtual field trips, or perform online research to learn more about a topic.

Materials

It is often a misconception that the more materials a school has—books, technology devices, tools, consumables, curriculum, you name it—the higher the student achievement is. And while schools with lots of resources, might have high performing students, it is not necessarily a causal relationship between the two. It is likely that schools with lots of resources have a large budget that not only allows them to purchase a plethora of products, it also allows them to invest in high quality teachers, professional development, and other areas that largely contribute to academic success. The reason I share this is because it's not about the amount of materials you have access to as a teacher—it's about how you use them.

Early in my career, I used to assign projects that maximized student choice. I wanted my students to have agency over what they learned, and how they demonstrated their understanding. However, it wasn't long before I noticed that my students really struggled with this. Part of the reason was because they weren't used to doing these types of projects, and the other part was that they simply had too many choices to make—which totally overwhelmed them. I quickly learned that I had to provide more structure to my projects that guided and supported them throughout the process. And the foundation of this structure was built on providing a select set of materials that would intentionally generate creativity.

As an example, during my first year as a technology teacher, I assigned the tower challenge where students competed in teams to construct the tallest freestanding tower. When I assigned this challenge, I made the mistake of allowing my students to use as many materials as they wanted. To my dismay, I found that students spent too much time arguing over what materials to use before they began designing their tower. The next time I did this challenge, I only allowed my students to use the following materials: six sheets of newspaper, 12 inches of masking tape, and one pair of scissors. I also encouraged them to draft a design of their tower before they started building. I discovered that by adding these constraints, they were able to work more efficiently, and more creatively.

I also made this same mistake when I allowed my sixth-grade science students to demonstrate their learning however they desired. I noticed that many students had difficulty getting started because they couldn't decide on how they wanted to showcase their learning. Because of this, I made the decision to assign a particular performance assessment to each project. Picture this, students had to create an edited video for the topic of moon phases, a tri-fold brochure for watersheds, and a song for the three laws of motion—just to name a few. And by the end of the year—after students had experience creating different artifacts and performances— they could choose their presentation method to communicate what they had learned in their final unit. So, as you assign projects to your own students, I highly recommend providing them with just enough materials and resources to kickstart their creativity.

Policies

Out of all of these constraints, I hear teachers complain the most about their school policies. I frequently hear the words, "I can't because ..." followed by a policy regarding specific learning standards, meeting benchmark requirements, or using school-wide curriculum. While these are all legitimate constraints, they are also opportunities that allow us to find creative solutions as teachers.

I remember watching Dr. Anthony Muhammad deliver a keynote presentation on a topic from his book, Transforming School Culture. During his keynote he shared an idea that has stayed with me after all these years. He presented an image on the screen that is similar to what I have recreated in Figure 1. Then he asked the audience a version of the following question, "Which of these factors do you believe has the greatest impact on student achievement? [4]" In order to answer this question, he requested everyone to use their smartphone or computer to respond to a digital survey on the online platform, Poll Everywhere. We all selected one of these options, which immediately displayed the results in real time. Not surprisingly, most people selected teachers as their answer.

.jpg) |

| Figure 1: Policies - Adapted from Dr. Anthony Muhammad |

The point that he so cleverly made was this—if we all collectively agree that teachers have the most significant impact on student achievement, then why do we spend so much time complaining about policies? As a teacher in a public school at the time, I completely bought into what he was selling. There was so much negativity in my school regarding the Virginia State Standards of Learning (SOL) Test and the policies that were associated with it. It was at that moment when I realized I had the power to positively influence the success of my students, and I could do it within the constraints of these policies. I made a promise to myself that I wouldn't let these policies overshadow the important work that I do—and that other teachers do—with students each and every day.

What I learned from this experience is that we have the ability to think of these policies—as well as other school policies—as constraints that challenge us to become better teachers. And that also challenge us to find creative ways to follow state and national guidelines, while also providing opportunities for our students to thrive in the classroom. Even though it is difficult, it is possible for students to learn the necessary information that is required of them to pass standardized tests, and develop their strengths and talents at the same time. To quote A.J. Juliani and John Spencer, "There is no guarantee that creative thinking will increase test scores, but who would you rather have take a test: a disengaged trained test-taker or a fully engaged creative thinker? [5]"

Constraints as Challenges

My intent with this chapter was to call attention to the idea that constraints can be advantageous if we think of them as challenges. We learned how Antoni Gaudi was able to use the constraint of his own knowledge and skills to revolutionize architecture. We looked at some of the most common restraints that are found in the classroom and found creative ways to innovate inside the box. And finally, we considered how we can apply calculated constraints to student assignments in order to unleash their creativity.

Whenever I teach a lesson, I like to think of myself as an engineer that uses the art and science of teaching in order to craft meaningful lessons for my students. This is because, "Engineers make things that work in the real world, within constraints of time, budget, and materials. Constraints make life interesting, and dealing with constraints creates opportunities for ingenuity and creativity” [6]. Similarly enough, I also like to think of our students as learning engineers—who use their available resources to creatively construct their own knowledge in the classroom.

If you find yourself in a school environment with many of these same constraints, I encourage you to unleash your own creativity to find innovative solutions for your students. Better yet, I challenge you to empower your students to come up with their own original solutions that meet their unique learning needs in the classroom. And the next time you design a lesson, assignment, or project, I urge you to introduce purposeful constraints that provide structure, support, and guidance to your students so that they can release their creativity for the world to see.

References

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment