Posted by

Bradley Lands

on

competence

confidence

culture

knowledge-able

learning

responsive

teaching

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

As an avid mountaineer and explorer, New Zealander Edmund Hillary climbed to the top of many mountain peaks before he reached the summit of Mount Everest in May of 1953. When he got the news that two men failed to reach the top on the same expedition, that didn't stop him. Two days later he and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first two people to conquer Earth's tallest mountain at 29,035 feet, and paved the way for about 4,000 other highly trained, daring climbers. What's more, Hillary was the first person to visit both the North and South poles and summit Everest, which landed him a spot on TIME's 100 most influential people of the 20th century [1].

What I find to be the most inspiring part about Hillary's story isn't the awe of his adventures, it was his passion for philanthropic ventures. In addition to writing nearly 12 books, Hillary founded the Himalayan Trust, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reducing poverty and improving the overall welfare of the Sherpa people by building schools, hospitals, and airfields [1]. And by the time he died in 2008, he had achieved his mission of improving the health, education, and well-being of this climbing community in Nepal.

How was Edmund Hillary able to achieve so much success in his lifetime? I believe that it was due to his elevated combination of curiosity and courage. He was able to reach Mount Everest's peak not only because his interest was piqued, but because he was able to overcome intense physical and mental adversity. And he was able to start a nonprofit education program not only because of his audacious ambition, but because he was able to indulge in his inexperience.

I share this anecdote because I hope it inspires you to develop these traits in your students, just as it inspired me. My goal in this section is to illustrate how the relationship between curiosity and courage impacts student learning. Based on my experience and research on this topic, I have found that the more inquisitive and fearless students are, the higher their learning outcomes are. Therefore, I am proposing that if we are able to help students increase their interest and conquer their fears, then they will be better positioned to gain and retain new knowledge and skills.

Looking back on my own education, I was never a student who was overly curious. I worked hard in school, and I got good grades. It wasn't until I read the book, Mindset by Dr. Carol Dweck that I realized I had boundless potential to learn anything if I put in the time and effort. This epiphany truly changed my entire outlook on life, and I became infatuated with the process of learning.

In an earlier post, I decided to use a stereotype to make a point about the relationship between one’s fear and their ability to learn and use technology. Just like the example of using technology, fear often gets in the way of learning any topic or skill. I’m sure you can think of a time when you might have been scared, apprehensive, or intimidated to learn something new. In the Inspiration section I shared a story of a time when I was afraid to use hand tools when working on a carpentry project with my dad. I know these experiences can be challenging, but they make us resilient as learners.

In the 15 years I have spent in the field of education, I have found that curiosity is the biggest driver when it comes to learning. This is probably why inquiry-based learning is such an effective teaching strategy to use with students. In her book, Dare to Lead, Brené Brown tells us that "curiosity is an act of vulnerability and courage." In fact, "Researchers are finding evidence that curiosity is correlated with creativity, intelligence, improved learning and memory, and problem solving" [1]. Brown also reveals that "A study published in the October 22, 2014, issue of the journal Neuron suggests that the brain’s chemistry changes when we become curious, helping us better learn and retain information. But curiosity is uncomfortable because it involves uncertainty and vulnerability” [2].

In contrast, I have also found that fear can be the biggest obstacle or deterrent to learning. I agree with Notter and Grant when they shared in their book, Humanize that "Nothing is more limiting to human beings than fear." What's more, it requires a significant amount of courage on one's part in order to overcome fear. Notter and Grant define courage as figuring out how to move forward in the presence of fear, which they claim is a hallmark of the human development process [3]. In other words, human beings have only been able to evolve and innovate due to our ability to rise above adversity, and conquer fear.

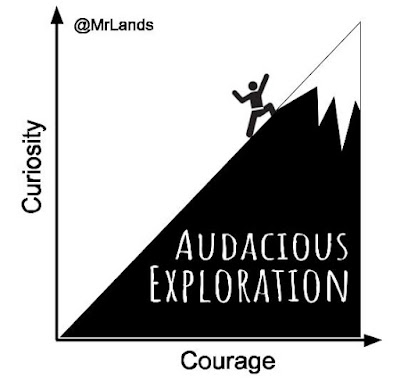

It is only when we create a coordinate plane with the x-axis representing courage, and the y-axis representing curiosity, can we clearly see the relationship between these two variables. If we examine the coordinates of the intersection of curiosity and courage, we begin to find interesting correlations between the two variables in each of the four quadrants, which I call "learning zones." (See Figure 1).

| |

|

In Quadrant I we have Audacious Exploration where curiosity is high, and courage is high. In Quadrant II we have Vigilant Inquiry where curiosity is high, but courage is low. In Quadrant III we have Apathetic Trepidation where curiosity is low, and courage is low. And in Quadrant IV we have Reckless Indifference where curiosity is low, but courage is high.

I would argue that the greatest potential for learning occurs in Audacious Exploration. This is what happens when curiosity and courage come together. When curiosity and courage are both high, students are able to take creative risks in their learning, and they often find themselves in a "state of flow" [5]. When students experience a state of flow, they tend to be so captivated by the learning activity that they seem to lose their awareness of time and space.

In January of 1990, Hungarian-American psychologist, Dr. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi published this idea of flow. "Csikszentmihalyi studied what he called optimal experiences, those rare moments in human existence when a person feels free of mundane distractions, in control of his fate, totally engaged by the moment" [4]. Csikszentmihalyi found that flow—a state of intense concentration—contributes to happiness and success when individuals are completely absorbed in the moment, and fully immersed in an activity that appropriately challenges them. As an example, "In his early research, Csikszentmihalyi interviewed chess experts, classically trained dancers, and mountain climbers, and he found that all three groups described flow moments in similar ways, as a feeling of intense well-being and control." [4]

When a student encounters a state of flow, the challenge of the learning task is slightly above their ability level—let's say at a 55 degree angle—which creates an optimal learning experience for them [5]. The challenge appropriately pushes their thinking, and they engage in productive struggle in order to successfully complete the learning task. What's more, this creates a personalized, differentiated learning experience for the child (See Figure 2).

.jpg) |

Figure 2: State of Flow Graph adapted from Csikszentmihalyi (1990) |

However, there are times when the challenge of a learning task is too high for a student's ability level. When this happens, Csikszentmihalyi tells us that a child can experience anxiety during the learning process [5]. This anxiety is the result of students recognizing that they don't have the knowledge and skills yet that are necessary in order to successfully complete the learning task. In these cases, we either need to scaffold the learning task by decreasing the challenge, while we help the student to increase their ability.

On the other hand, there are also times when the challenge of the learning task is too low for a student's ability level. When this happens, Csikszentmihalyi found that a child can experience boredom during the learning process [5]. This boredom is the result of students recognizing that their knowledge and skills exceed the challenge and the learning task is too easy for them. In these cases, we need to increase the difficulty of the learning task so that it is more appropriately challenging for the student.

The most challenging—yet rewarding—part of being a teacher is trying to find the perfect balance between challenge and ability for every child. But when we know our students' strengths and weaknesses—and when we empower them to make choices to take ownership over their learning—the balance tends to organically fall into place. This is because when students have agency to ask their own questions, to use resources and strategies that are appropriate for them, and to demonstrate their understanding in a way that makes sense to them, they are able to naturally differentiate their learning.

In an attempt to make a comparison between Audacious Exploration and the state of flow, I'll use the analogy of climbing a mountain to represent any given learning task—just as Csikszentmihalyi studied mountain climbers in his research. If we were to transpose Figure 2 directly on top of Figure 3, you would notice that the slope of the mountain, and the state of flow are roughly the same angle. This is because Audacious Exploration has the ideal balance between curiosity and courage that is needed to maximize learning, which can often lead to a state of flow. Continuing to use the analogy of climbing a mountain, let's unpack each of the four learning zones to gain a deeper understanding of their impact on education.

|

| Figure 3: Audacious Exploration |

Audacious Exploration

When curiosity is high, students become interested, engaged, and have intrinsic motivation for learning. When courage is high, students are empowered, courageous, and feel emotionally, intellectually, and physically safe. In this zone, students aren’t afraid of making mistakes along their learning journey, and their innate inquiry will sustain their effort. Students in this zone ask meaningful questions, utilize applicable resources, and are excited to showcase their learning and understanding. This is ultimately where we want our students to end up during any learning task. To support these students, simply get out of their way and provide structure, feedback, and encouragement as needed.

If students in Audacious Exploration were tasked with climbing a metaphorical learning mountain, they would be super curious about what the view from the top looked like. They would also have the confidence and courage to begin climbing the mountain with a backpack filled with just the necessary gear and resources that they need. They would understand the interdisciplinary relevance of physical fitness, elevation, geography, culture, and weather. And their drive and determination would carry them to the top of the mountain where they would get to enjoy the breathtaking views that they so eagerly anticipated.

Vigilant Inquiry

The second most effective zone for learning occurs in Vigilant Inquiry. This is where curiosity is high, but courage is low. This can be a particularly effective learning zone, as students have an elevated degree of wonder, but they are more cautious with taking creative risks. In this zone, students might not feel safe enough to apply themselves as much as they could. Some reasons for this might be that they don’t feel physically safe, they lack self-confidence in their ability, or they might be afraid to make mistakes. Students are still able to learn, but they don’t put forth their best effort, and do just enough to get a good grade.

If students in Vigilant Inquiry were tasked with climbing the mountain, they would also be really excited to reach the top, but might be nervous due to the dangerous nature of the activity. They might be brave enough to begin the climb, but they probably wouldn't make it to the summit. These students would also overpack so they would be prepared for every possible situation. This would ultimately weigh them down, and their exhaustion would prevent them from reaching the summit. These students would learn a lot on their climbing journey, but they wouldn't reach their full potential, and they wouldn't get the intrinsic reward of being able to enjoy the view from the peak.

To support students who are in this zone, I recommend building strong relationships and reassuring them that your classroom is a safe learning environment. I also recommend differentiating the learning task by providing appropriate scaffolding. These strategies will help them to build the courage that is needed to maximize their learning.

Apathetic Trepidation

The least effective zone for learning lies in Apathetic Trepidation. In this zone, students have little to no interest in the lesson topic, and they are apprehensive about the learning task. This can cause them to become a passive learner, and put minimal effort into the lesson. One possibility could be that the learning task is too challenging, which can cause anxiety; or the learning task is not challenging enough which can cause boredom. Another possibility could be that students do not find the lesson topic meaningful or relevant to them. Students in this zone are arguably the most challenging, because they will likely display off-task behavior, or shut down entirely.

If students in Apathetic Trepidation were tasked with climbing the mountain, they would have little to no desire to reach the summit. They might also think that the climb is way too dangerous, or believe that they lack the physical and mental capacity to climb the mountain. These students wouldn’t even bother to bring a backpack, because they don’t have any intention of making the climb. Because these students would just stay at the base of the mountain, they would only learn about the experience from watching their classmates, and hearing their stories.

To spark curiosity in these students, I suggest presenting the lesson topic in a way that is culturally responsive and applicable to the real world. To raise courage in these students, I recommend establishing rapport and earning their trust. Building these types of positive connections in the classroom can pay dividends by creating a safe learning space where your students will feel more comfortable taking risks.

Reckless Indifference

The second least effective zone for learning is Reckless Indifference. In this zone, students are generally uninterested in the lesson topic, but they are extremely daring with the learning task. When students are in this zone, they can become thoughtless and impulsive, which can easily disrupt their learning or the learning of their classmates.

In my experience, I have encountered students who exhibit off-task behaviors such as going on learning tangents, acting inappropriately, or purposefully trying to derail the lesson. Sometimes students enter this zone when they have difficulty making a connection to the lesson topic, or they don’t see a purpose in learning the task. If you have ever heard a student ask, “Why do we have to learn this?” or "Is this going to be on the test?" then there is a good chance they were in this zone.

If students in Reckless Indifference were tasked with climbing the mountain, they wouldn’t understand the vision and mission of the expedition, but they would be ecstatic that they are on a field trip. They would fully believe in their physical ability to climb the mountain, but might lack the purpose and navigation to get to the top. These students probably wouldn't bring a backpack with them, because they either don’t know what to bring, or they don’t think they need any gear or supplies. And because these students would try to carelessly climb the mountain with minimal preparation, they could end up physically hurting themselves, or their classmates. The only thing they would learn from this experience is that it was pointless, and they could have just Googled images of the view from the summit.

To support these students, I suggest trying to explain how they can directly benefit from the lesson. Just like in Apathetic Trepidation, if students are able to attach meaning and relevance to the learning task, they might be more willing to put forth the effort. I would also try different methods to ignite their curiosity such as using an intriguing prompt to get them thinking. This could be in the form of a surprising statement, an image, video, or artifact to initiate their inquiry.

The Pursuit of Audacious Exploration

At this point we have clearly established that curiosity and courage are two major factors when it comes to learning. Curiosity fosters learning, whereas, fear discourages learning. I feel like the following quote perfectly captures the impact that these different learning zones have on students regarding their curiosity and courage.

"If you are not willing to learn, no one can help you. If you are determined to learn, no one can stop you." - Zig Ziglar

As teachers, we try our absolute best to motivate, inspire, and influence students. However, we cannot make them learn—we can only try to provide the conditions in which they can learn. In other words, "you can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him think" [6]. My hope is that we as educators help guide our students into Audacious Exploration as they engage in the learning process, just as Edmund Hillary audaciously explored Mount Everest, and his fortitude in philanthropy. If we are able to provide students with these conditions in which they can learn best—curiosity and courage—then we will be setting them up for success.

Reference

Comments

Post a Comment